How do you map a 100-mile nature corridor?

By Alex Briggs - 02 May 2023

Perhaps first we should ask, why is a corridor important? Traditionally, conservation has tended to focus on restoring and protecting key areas, such as nature reserves. These core areas are vital for maintaining sustainable populations of wildlife species. However, as human land use has intensified, protected areas have become islands, isolated in the wider landscape. Gradually, species ranges become restricted to these areas, leading to declines, low genetic health, and eventually to local extinctions.

Joining the dots

The aims of Weald to Waves are partly based on the 2010 review Making Space for Nature, led by Sir John Lawton, which concluded that England’s wildlife sites need to be “bigger, better and more joined up”. Establishing corridors that reconnect the landscape is a crucial step in halting wildlife declines and supporting nature recovery.

Powered by data

Choosing the route for a wildlife corridor across one of the most populated regions of the UK was a huge challenge. We approached the task using mapping to consider as many factors as possible to create a sustainable project that would balance the needs of both humans and wildlife. Our maps included a wide range of datasets including information from our partners, including Natural England, the South Downs National Park Authority, Sussex Wildlife Trust, and other conservation organisations including Sussex Biodiversity Records Centre, Buglife International, the Rivers Trusts, DEFRA and the National Trust. Other datasets include maps produced using advanced Geographic Information Systems (GIS) techniques such as habitat maps produced by running machine learning algorithms on satellite imagery and vegetation mapped by LiDAR, to reveal opportunities for people and nature.

Balancing opportunities for wildlife and humans

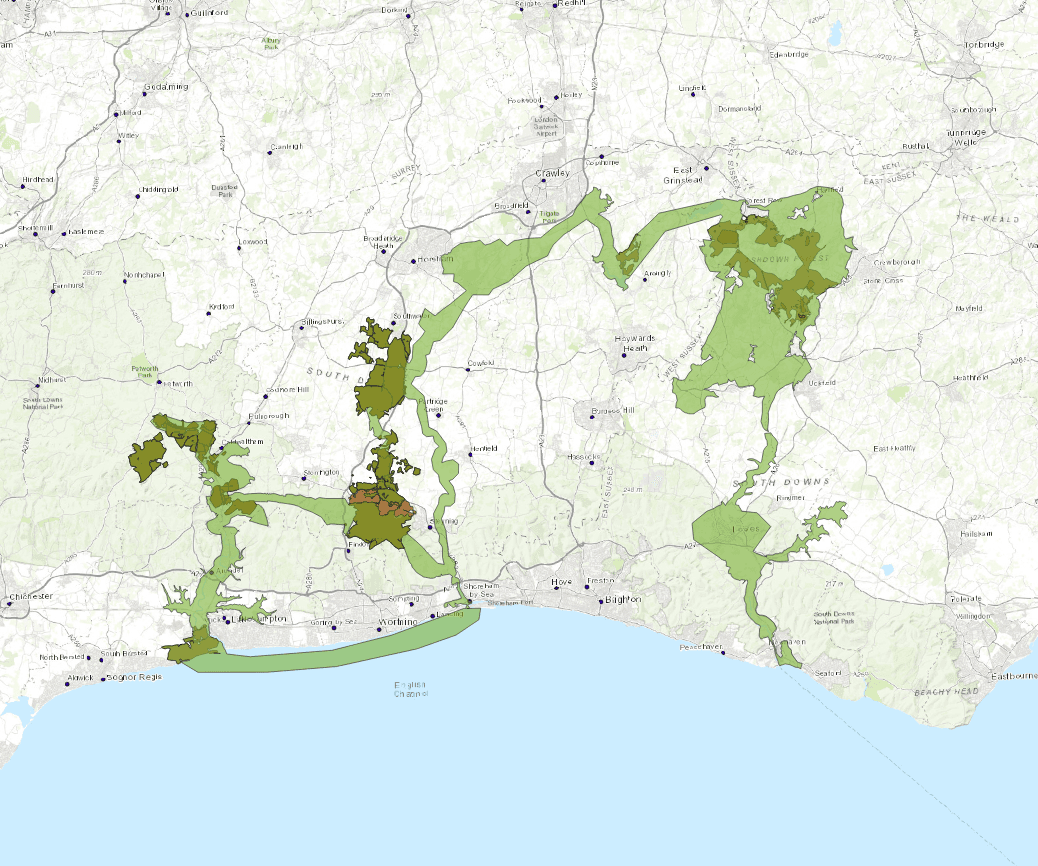

At the very least, the route of the corridor needed to connect the landholdings of the project’s seven founding members (fig. 1) and follow the rivers Adur, Ouse, and Arun to the sea. Rivers are natural corridors, providing strips of vital habitat where blue and green collide.

Fig. 1: Map shows the landholdings of the seven founding members of the Weald to Waves corridor

Fig. 1: Map shows the landholdings of the seven founding members of the Weald to Waves corridor

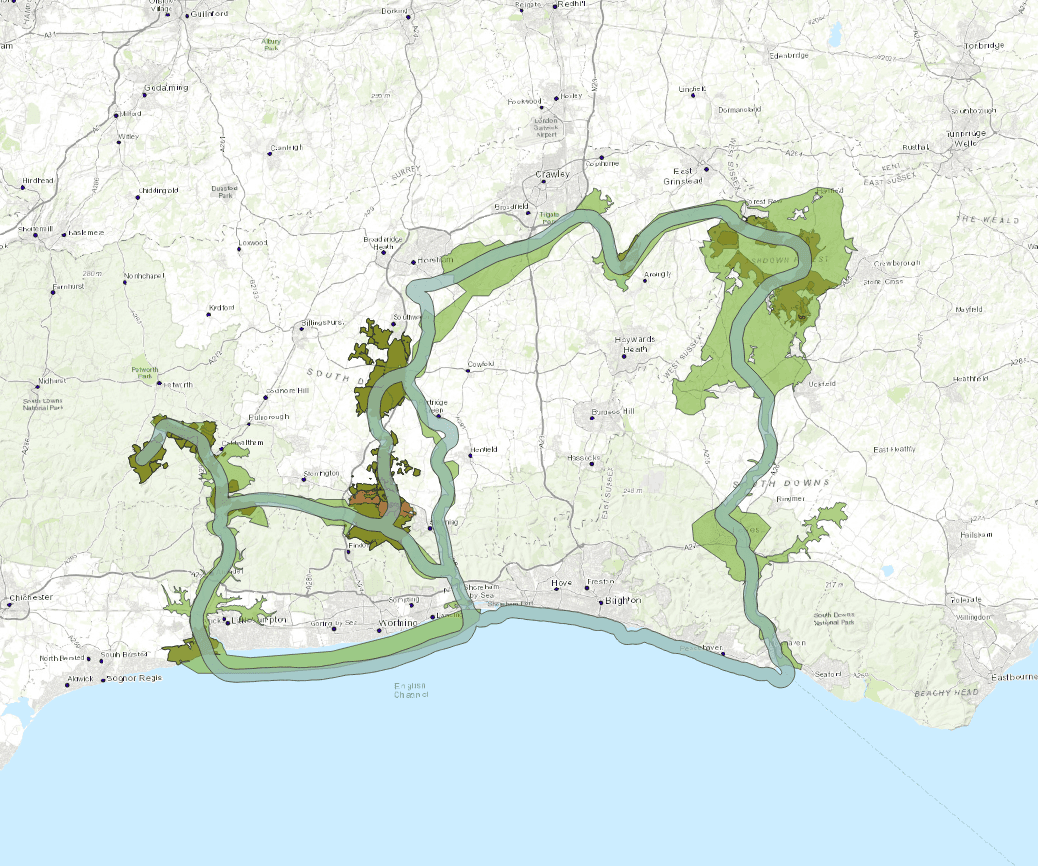

To balance the best routes for both humans and wildlife, the corridor was divided into two zones, a 1km wide Core Zone and a 5km wide Radiance Zone. The Core Zone represents the best opportunities for wildlife connectivity. It broadly follows Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (fig. 2), identified by the Sussex Local Nature Partnership as important areas for improving landscape connectivity. On a local scale, the Core Zone joins up the UK’s Priority Habitats (as defined by Natural England), along with protected areas, nature reserves, Sites of Special Scientific Interest and local wildlife sites (fig 3, green route). Similarly, the Radiance Zone *(fig. 4, yellow route) represents the best human opportunities by bringing local people into the corridor, including urban areas, greenspaces, and areas with limited access to the outdoors.

Fig 2: Map showing the Biodiversity Opportunity Areas identified by the Sussex Local Nature Partnership as important areas for improving landscape connectivity plotted with the seven founding members' landholdings

Fig 2: Map showing the Biodiversity Opportunity Areas identified by the Sussex Local Nature Partnership as important areas for improving landscape connectivity plotted with the seven founding members' landholdings

Fig 3: Map shows the Weald to Waves Core Zone (blue/green route overlay) joining up the UK’s Priority Habitats, along with protected areas, nature reserves, Sites of Special Scientific Interest and local wildlife sites.

Fig 3: Map shows the Weald to Waves Core Zone (blue/green route overlay) joining up the UK’s Priority Habitats, along with protected areas, nature reserves, Sites of Special Scientific Interest and local wildlife sites.

Fig 4: Map shows Weald to Waves corridor 1km-wide Core Zone and 5km-wide Radiant Zone

Fig 4: Map shows Weald to Waves corridor 1km-wide Core Zone and 5km-wide Radiant Zone

Defining the route and boundaries of Weald to Waves was at times a challenging prospect, but we had to accept there are no right (or wrong) answers to this problem. There is no single route that represents the best connectivity for declining wildlife species. We need to improve connectivity for nature everywhere, across every landscape. Weald to Waves hopes to inspire new conservation efforts, and to help connect up existing groups, organisations and projects to create a corridor of nature recovery in a project that can grow and be applied everywhere.

Explore more:

Explore our interactive maps to learn more about the corridor

Making Space for Nature, Sir John Lawton