Rewilding our seas

By Cathy Robinson - 03 July 2023

When you think of rewilding, you might imagine lush scrublands brimming with wild flowers and dancing with butterflies and bees. Maybe there’ll be some free ranging cattle trampling and nibbling. A rewilded marine environment is harder to picture. But just as soils and land-based ecosystems have become degraded, so have marine habitats. Sewage is regularly discharged into rivers and seas, agricultural run-off upsets the natural balance of the water, while trawling destroys the seabed and the kelp forests that once flourished.

Rewilding requires space for natural ecosystems to regain a foothold. Marine ecosystems involve complex layers of seabed sediment, microscopic plankton, seaweeds and algae, a wide diversity of fish and invertebrates, marine mammals, and sea birds. The seismic shocks to this fragile system from human activity have long been overlooked and underestimated.

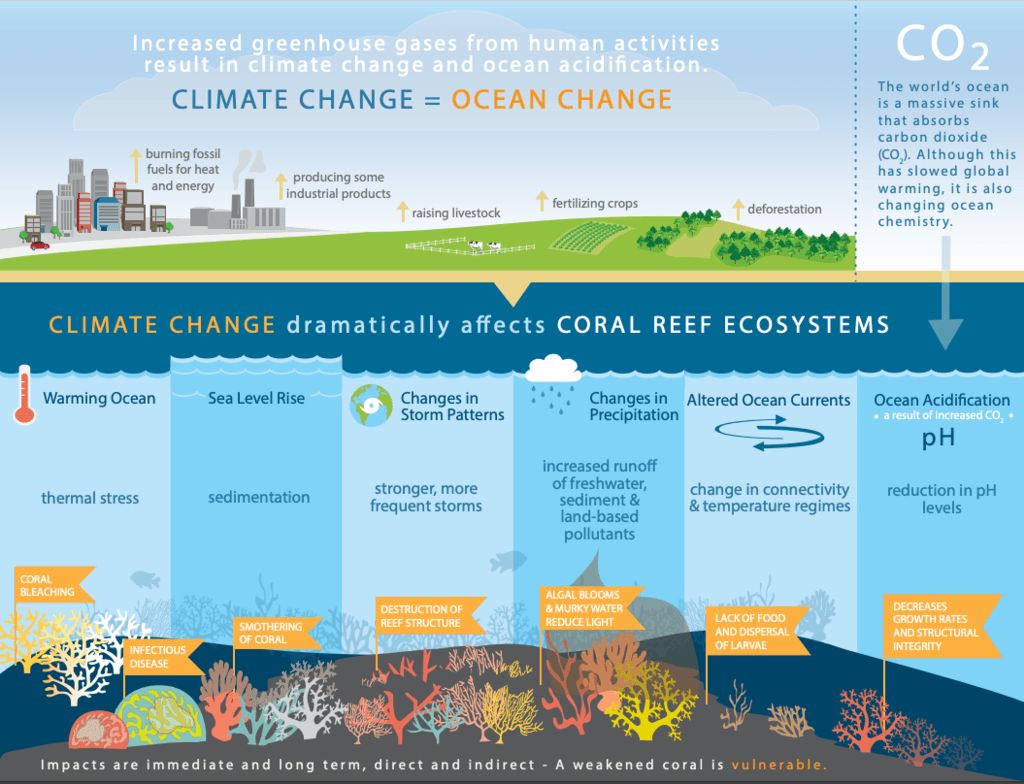

Our marine habitats cover over 70% of the planet. Oceans absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, which alters the pH of the water, making our seas more acidic – and it’s happening faster than at any other time in history. It’s estimated our oceans trap around a quarter of all carbon emissions. While this removes excess carbon from the air, increased acidity is is bad news for our marine life. The reduction in calcium in the water is changing the shells and skeletons of marine creatures and damaging coral, which, under severe acidification, can start to dissolve. This leads to serious repercussions higher up the food chain, upsetting the delicate balance of the marine ecosystem.

Image 1 - Pterapod shell dissolved in seawater adjusted to an ocean chemistry projected for the year 2100. Source: US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Environmental Visualization Laboratory

Image 2 - Source: US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Ocean Service

The Weald to Waves corridor doesn’t stop when it reaches the shore. Ambitious initiatives like the Sussex Kelp Recovery Project aims to restore 170km2 of lost kelp forest in the Sussex Bay. Kelp was once widespread off the Sussex coast but is now almost completely lost and what remains is fragmented. These underwater forests were a critical part of our marine wilderness, providing habitat for a vast array of marine species. Kelp can significantly contribute towards decreasing climate change as it’s estimated that kelp forests can store up to twenty times more carbon than land-based trees.

“It’s estimated that kelp forests can store up to twenty times more carbon than land-based trees.”

Any hope for wilder waters relies on clear and decisive action on land. Responsible farming along the corridor and across Sussex, especially adjacent to water courses, can reduce fertilisers and pesticides reaching our ocean. River recovery work across the three river catchments in the corridor is helping to restore the health of the river banks and in so doing reduce the volume of contaminants flowing into the ocean. There are efforts to restore salt marsh and protect globally rare shingle habitats found along the Sussex shore. The brilliant **Sussex Bay ** initiative aims to create restored, abundant seas and intertidal rivers in Sussex, with a focus on sustainable fishing and the development of a blue carbon code. All this is an investment in the interconnectivity of our land, rivers and seas.

As we head into National Marine Week, there is a call for joined-up action to restore our natural world beneath the waves. Join the corridor today and pledge your land, time or support to revive our seas and the ecosystems that we rely on.

Learn more:

Long read Rewilding the Sea by Charles Clover Quick read Introduction to Marine Rewilding by Rewilding Britain Watch Introduction to Rewilding the Sea(4 mins) by the Blue Marine Foundation